Laura Nelson

Progressive Forage

Focus on high-quality forage, secure a long-term market

Eric Sheffer knew he wanted to make his life in agriculture.

The trick for the sixth-generation New York farmer would, of course, be figuring out how to make a living in it.

His father had an off-farm job and had transitioned their dairy to raising crops and replacement heifers to accommodate that, but Sheffer wanted to be there full time. He saw an opportunity to make it happen by transitioning back to dairying and utilizing the forage-based model his father used with the replacement heifers. In 2008, Sheffer’s Grassland Dairy LLC got its start with 100 cows and 115 acres of pasture on the heavy, loamy-soiled hills, plus 300-some acres of farmed forages.

With his dad’s help, they built many of their own foundational dairying facilities, and acknowledged the first few years would be lean. The key would be getting by with the slimmest inputs possible while meeting calculated output goals. Even so, the national economy made for a shaky entrance into a new business venture.

“2009 was a really, really tough year. We were wondering if we could hold this together,” Sheffer says. But with up to 40 inches of annual precipitation, they had an invaluable resource on their side: readily available, high-quality forage.

“We just had to focus on what we could do well,” he says. “Making milk with grass.”

Sheffer entered the conventional dairy industry at the zenith of organic milk production. The USDA showed the number of certified organic milk cows increased nearly 25% between 2000 and 2005. Between 2002 and 2007, the number of organic dairy farms nearly tripled. But with conventional feed contracts within 5 miles of the farm, and a need to start with the smallest input possible, it didn’t make sense to jump into the organic market immediately.

The milk market came around to a more positive swing by 2014, allowing the family to pay off debts and reinvest to expand their land base. They saved and invested, slowly growing to 235 cows on 250 acres of grass and 350 acres of forage cropland over the next seven years. Then their opportunities to look into alternative production and marketing felt more realistic.

“We wanted to work with someone who knew we had something to offer,” Sheffer says. “In the conventional market, we felt like we had nothing to offer – we’re milking 235 cows in New York – we can’t compete with the big dairies in the conventional market. But with organic, we had something to offer.” They had grass.

Making the transition

Fay Benson was a dairy farmer near Groton, New York, with 50 cows when the organic milk market first exploded. He, too, recognized that a small dairy would struggle to compete in an increasingly concentrated commodity market. He transitioned his dairy to organic production and shipped his first organic milk in 1997. In seven years, the financial viability of the organic market allowed him to pay off his farm debt. He then joined Cornell’s Cooperative Extension where he established the New York Organic Dairy Initiative to help other small farms transition to the organic market.

“It’s a bit of a chess game,” Benson says, outlining the three-year process to earn certified organic status. “It’s easier if you’re already using a lot of forages, and Sheffers were, so that helped.”

Farmers manage the land using organic practices for three years, and cows are required to consume an organic diet for one full year before they qualify for organic production. Organic grain often costs up to three times what conventional corn does; if grain is rationed back, forage quality has to be exceptional in order to compensate for lost energy.

“It’s insanely hard,” Sheffer says. “We knew we would miss the urea, but we found transitioning the cows was way harder than transitioning the land.”

When they removed the cows’ non-organic mineral pack with a feed efficiency additive, milk production dropped by nearly 3 pounds overnight.

Milk contractor Stoneyfield Organics helped the family through the financial transition as part of a long-term, cost-plus model contract. Before making the organic transition, Sheffer sought out potential milk handlers from several companies before brokering their contract with Stoneyfield.

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it,” Benson says. “Eric’s not the kind to say, ‘I think this might work.’ He knew his numbers, and he knew what they could do. Whatever kind of system you’re in, good management will be what does the job best.”

With Stoneyfield’s financial backing, Benson’s organic expertise, consultations with New York state grazing specialist Karen Hoffman and plenty of organic dairying peers and family support, Sheffer starting scouting for organic feed sources to complement his forage availability.

The starch and fiber content of corn silage would be replaced with organic, high-moisture corn, boosted by small grains like organic triticale, millet, wheat or barley to help compensate for the loss of the rapidly fermented silage starch. Soybean meal may add the necessary protein and energy to stored forages. Sheffer says they’ve considered growing their own sudangrass and sorghum to meet those needs, also.

But for a small, organic dairy herd, the most vital part of the ration is forages.

“To be successful in the organics world, you have to have enough pasture. If you don’t have pasture, you’re never going to make it unless you’re milking thousands of cows,” Sheffer says.

Cool-season grasses dominate their forage mix, which is cross-seeded with a combination of red clover, white clover, orchardgrass, ryegrass and meadow fescue. A combination of permanent perimeter fencing, laneways and polywire with step-in posts make paddock breaks to graze their 250 acres of pasture with intensity. Lactating cows are turned into a fresh paddock with at least 10 to 14 inches of growth every 12 hours, and the aim is to leave the paddocks with around 4 inches of growth remaining.

“If you want to improve your grazing efficiency, you have to keep them moving,” Benson says. This allows the cows to do some of the work of manure spreading and leaves residual cover for regrowth in the proper rest period.

“To do what we’re doing, we have to have the prime-quality forage,” Sheffer says. Ideally, Sheffer says he would like lactating cows consuming forages with 190 to 200 relative feed value (RFV), but that’s rarely available in the Northeastern organic market. They’re more likely to find 120 to 160 RFV and make do, but higher feed value means higher production. They’re relentlessly in search of the highest quality possible.

When a niche becomes mainstream

When Sheffer began the transition to organic production in 2014, he says, “The market was screaming for more organic milk.”

But in the last three years, the 20-year growth of the organic milk market has slowed and prices have declined in response to saturated demand. Between 2017 and 2018, 2,731 licensed dairy farms went out of business in the U.S., most of which were smaller Northeast or Midwest farms. Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, New York, Michigan and Ohio were hit the hardest, and the organics markets wasn’t as insulated from tumbling milk prices as it has been in the past. Benson and Sheffer both pointed to the entry of larger Western dairies into the market.

“I got out of the conventional market because I know I can’t compete there. I feel like I’m in the same spot now, and that’s frustrating,” Sheffer says.

So what’s next for a small dairy herd looking for a niche they can remain competitive in?

Benson pointed to a complete grass-based market as a potential, even more stringent option. It’s still paying a premium above organic production, but the loss of production can be staggering. A grass-fed dairy cow in their part of the Northeast would require approximately 6 acres of land per animal to harvest forage from, compared to a minimum of about 2 acres per cow in an organic system where even 80% of the diet is forage.

A cow with 20% of her diet comprised of high-quality grains may produce around 15,000 to 18,000 pounds of milk per year, whereas a solely grass-fed cow may drop to 9,000 to 10,000 pounds or far less, depending on the forage quality. Of the roughly 700 organic dairies in New York, Benson says about 100 of them are grass-fed, and those typically account for the smallest dairies in the state. It’s an exceptionally risky niche.

Regardless of the market, Benson says, the small, organic farms that are still profitable are the ones producing their own high-quality forages.

Sheffer says they looked into the all-grass system when they transitioned to organic, but chose to focus on one change at a time. They culled their herd to move into the organic market, but the cows have almost recovered production to their conventional years. Their goal is to return to the 235-head herd mark, but for now, Sheffer says he’s more interested in building his grass base than his cow herd.

“To some extent, we’re in a constant cycle of these ‘ah-ha’ moments, but the ‘ah-ha’ is almost always that we have to get back to basics,” Sheffer says. “The basics are always about getting back to the grass, always putting our money back into the grazing base. It’s so easy to get caught up in trying to get really high-production-minded, but at the end of the day, investing in the grass is our best return.” end mark

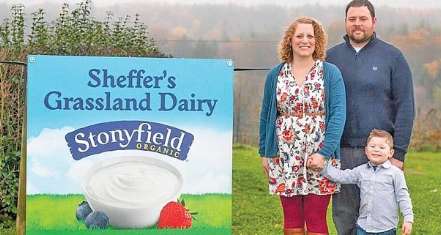

PHOTO 1: Eric, Jillian and their son Jackson are proud organic milk suppliers and continue to look for opportunities within their market.

PHOTO 2: Eric is pictured with his wife, Jillian, and his parents, Wally and Kathy Sheffer.

PHOTO 3: “To be successful in the organics world, you have to have enough pasture. If you don’t have pasture, you’re never going to make it unless you’re milking thousands of cows.” Photos provided by Eric Sheffer.

Laura Nelson is a freelance writer from Big Timber, Montana